– rising prosperity (and smashed avocado) versus housing affordability

Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP

Australia’s property fascination

Australians have long had a fascination with property. It’s evident in waves of speculative booms and busts that periodically grip our cities. For example, this was observed over four decades ago in relation to Sydney and documented by M.T. Daly in his book ‘Sydney Boom Sydney Bust’ which was published way back in 1982:

“City land booms have always been a snare of the people of the Australian colonies” and “despite various efforts of governments, the [Sydney real estate] system seems to have run out of control and the inflated values have become institutionalised”.

Since then, of course the fascination has arguably grown more intense facilitated by more ready access to data on the property market. But it’s also historically evident in relatively high levels of home ownership in Australia, particularly in the post-World War Two period. Since the mid-1960s, though, the home ownership rate has declined as documented in a fascinating report by the well-known demographer Bernard Salt together with AMP entitled ‘What wealthy means to Australians in 2023’.

Peak home ownership

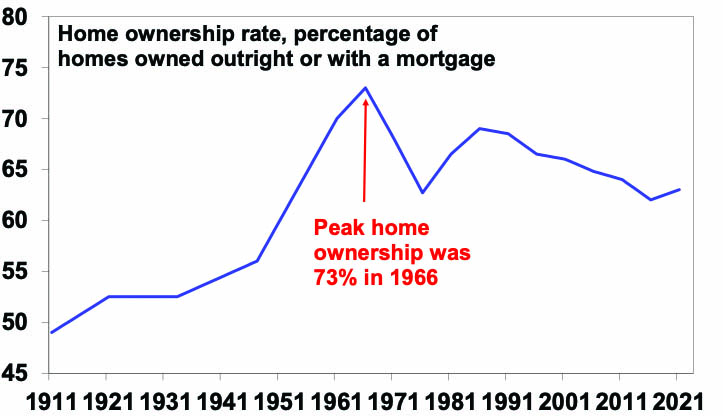

In my view, the most interesting chart in the report is that of home ownership based on ABS Census data dating back to 1911 that Bernard Salt and his team discovered peaked around 1966. Just before World War One, Australia’s home ownership rate was just below 50%, but from even this relatively high rate it surged in the post-World War Two years to reach a peak of 73% in 1966 as home ownership was seen as delivering financial security after the malaise of the Great Depression and World War Two. As the report notes, at the time it was all about “getting married, having kids, buying a house and holding a steady job”. Retirement planning was rarely on the radar with life expectancy at around 70 in the late 1950s and early 1960s. In the aftermath of the Depression and World War Two, the concept of wealth was seen as tied up to owning a home. However, from the peak in 1966, housing affordability has trended down to now being around 63%. The question is whether this decline reflects deteriorating housing affordability flowing from years of property booms, leading to a fading in the “Aussie dream” which is centred on home ownership or whether it’s something deeper.

Australian home ownership rate, 1911-2021

Source: ABS Censuses, Bernard Salt/The Demographics Group, AMP

A lot has happened since 1966

The natural inclination is to think that the fall in the home ownership rate is all due to worsening affordability. However, the Australia of today is radically different to that of 1966 and this has surely had a big impact as the report points out.

-

More years spent in education, people starting work further into their twenties, the increasing importance of career, rising female participation in the workforce, and a desire for more experiences and travel have all seen family formation pushed into the late twenties.

-

Starting with the baby boomers, subsequent generations have not felt the same need for the security offered by home ownership that their forebears felt in the mid-1960s. This partly flowed from dimming memories of the travails of the Great Depression and World War Two, rising levels of economic prosperity, greater choices for spending with the growth of travel and the café culture (Bernard Salt’s “smashed avocado on five grain toast”) and a perception, based on seeing their parents experience, that owning a home is not necessarily the way to happiness.

-

Related to this, there is an element of Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs” at work here. In Maslow’s hierarchy the first set of needs is physiological (eg, food and shelter), then safety and security (eg, health, employment and property), followed by love and belonging (eg, friendship and family), self-esteem (eg, confidence and achievement) and finally self-actualisation (eg, morality, meaning and inner potential). In the post war years, the focus for many Australians was on physical needs including shelter and a perception that this will provide safety and security. Today many still struggle with this but arguably the prosperity seen over the last 50 years has seen many more move on to focussing on self-actualisation. Witness the growth of books and material directed to this in book shops and online. In 1966 it was only just starting to become a thing with hippies trying to seek enlightenment. For some, individual freedom may not be seen as consistent with the financial commitment required by a mortgage.

-

Increased life expectancy – such that a retiree today may spend 25 years in retirement but maybe only 5 in the 1950s – and the growth of Superannuation from the early 1990s meant increased focus on retirement and wealth beyond the home.

-

Increased diversity in terms of cultures & sexual orientations may have reduced the perceived importance of home ownership for some.

The combination of these considerations has likely contributed to some diminution in the importance of home ownership as a measure of wealth and an underpinning of security in contrast to the ‘make do/Depression generation’ and to a lesser degree their baby boomer children. And demographics and starting careers later in life have pushed the desire for home ownership out from the early twenties to late twenties or thirties.

But what about housing affordability?

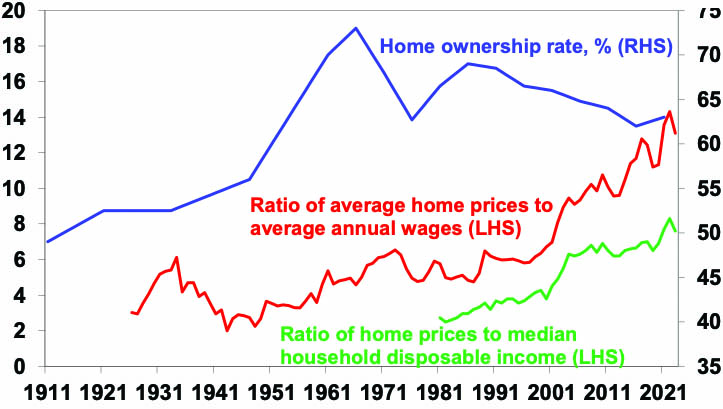

However, at the same time it’s hard to see housing affordability not impacting too. Trying to define housing affordability is always a bit of a challenge given the influence of house prices, income, interest rates and beneath that whether allowance is made for the rise of two income households and the increased availability of debt. But to keep things simple, it’s pretty clear that housing affordability has deteriorated massively since the 1990s. The first chart below shows the home ownership rate against two measures of housing affordability: the ratio of average home prices to average annual wages (in red); and the ratio of home prices to median household disposable income (green). The latter takes account of the rise in two income households, but data is not available before the 1980s. But the message from both is that since the 1990s there has been significant rise in the ratio home prices relative to incomes. Prior to the mid 1990s average home prices ranged around two to six times annual wages but since then it’s steadily increased to around 14 times. Similarly, the ratio of home prices to median household disposable income has blown out from around four times to eight times.

Home ownership versus home prices relative to incomes

Source: ABS, Bernard Salt/The Demographics Group, CoreLogic, AMP

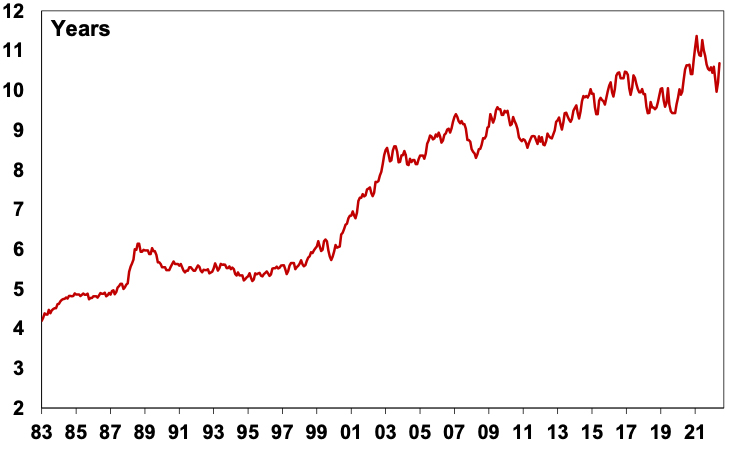

Yes, interest rates are still lower than was the case in the 1980s and 1990s, but this has been reflected in higher price to income ratios. Another measure related to housing affordability is how long it takes to save for a deposit to enter the property market. For someone on average full-time earnings it now takes around 10 years to save a 20% deposit to buy an average property compared to around five years thirty years ago.

Years it takes to save for a 20% deposit

Source: CoreLogic, AMP

The downtrend in home ownership over the last three decades has correlated with the deterioration in housing affordability as measured by home price to income ratios and the increasing time it takes to save for a deposit. So, housing affordability has likely contributed to the decline in home ownership along with the factors mentioned in the previous section. Disentangling their relative importance will be hard. The increase in the time it takes to save a deposit may also have accentuated the demographic factors referred to earlier – notably starting a family later in life – in delaying home ownership. Maybe the modest rise in home ownership in the last Census reflected the delayed start to family life.

Should we worry about falling home ownership?

To the extent that falling home ownership reflects understandable choices around demographic trends, prosperity and diversity we shouldn’t be too concerned. But it likely also partly reflects the impact of deteriorating housing affordability and this is something we should be concerned about as it is driving increasing inequality including across generations and if it persists it could threaten social cohesion.

What can be done to boost housing affordability?

So, what can be done to boost housing affordability? Much has been written on this over the years without much progress. And despite some efforts by governments (echoing M.T. Daly’s comments two generations ago) they have clearly not been successful although I suspect this is because they have not been comprehensive or forceful enough. Ideally government policy should involve a multi-year plan encompassing local, state and federal governments. My shopping list on this front includes:

-

Build more homes – relaxing land use rules, releasing land faster and speeding up approval processes, encourage build to rent affordable housing and greater public involvement in provision of social housing.

-

Matching the level of immigration to the ability of the property market to supply housing. We have clearly failed to do this following reopening from the pandemic, and this is now evident in severe supply shortfalls.

-

Encouraging greater decentralisation to regional Australia – the work from home phenomenon shows this is possible but it should be helped along with appropriate infrastructure and of course measures to boost regional housing supply.

-

Tax reform including replacing stamp duty with land tax (to make it easier for empty nesters to downsize) and reducing the capital gains tax discount (to remove a distortion in favour of speculation).

Policies that are less likely to be successful include: grants and concessions for first home buyers (as they just add to higher prices); and abolishing negative gearing which would just inject another distortion in the tax system and could adversely affect supply – although there is a case to cap excessive use of negative gearing tax benefits.

Source: AMP Capital May 2023

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591, AFSL 232497) and AMP Capital Funds Management Limited (ABN 15 159 557 721, AFSL 426455) make no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.